There is an answer to why this mindset exists. In short, journalists view advertising as a hallmark of "yellow journalism". Delos F. Wilcox, Ph. D. gives us the answer we need on page 91 of a book he wrote titled "The American Newspaper: A Study in Social Psychology". Published in 1900, originally in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, (I bring this up because of it's seemingly odd page numbering) there are 18 pages (out of 36) that contain the word "advertisements", that's practically 50% of the book. Starting on page 90:

Newspaper competition is, as we have seen, most severe in the largest cities, and there also the need of a new development of social consciousness is most pressing. Weekly and monthly journals appeal to a more widely scattered constituency, and for that reason do not supply to the city man even imperfect summaries of city news and municipal doings. For such summaries he must depend on himself or on municipal reports. Annual reports for free distribution are usually published by the large cities. Two American cities, New York and Boston, publish a daily or weekly "City Record," containing an account of all municipal business. These two cities also have instituted statistical bureaus for the collection and distribution of what we may call general municipal news. In Cleveland, at least, bulletins of important events are posted daily in the public library. In another direction also government is encroaching upon the field of the newspaper. In the establishment of public employment bureaus under state authority in Chicago and some other cities, we see an entrenchment upon the ''want ad'' columns of the daily newspaper. Is it at all unlikely that, following out these lines of activity, government, particularly in cities, will sooner or later put into the field newspapers to cover at least the news of local business and politics and be available for use in the public schools, the public libraries, the city offices, and elsewhere? If such journals could be kept free from factional control and from the debauching influence of irresponsible newspaper competition, they would be of great service in the education of the "public'' and in the control of private journals. But let no one imagine that government operation is here prescribed as a panacea for the evils of irresponsible journalism. Mr. Hearst has worked like a hero to make the New York Journal the yellowest and most successful journal in the United States. Practically, he "endowed" yellow journalism. The endowment scheme for newspaper reform is not generally accepted as practicable. There is a feeling that journalism should be a business, and that news-gathering and distribution should pay for itself. Those who object to the endowment plan should, however, reflect upon the question whether or not the public has not already been "endowed" by someone when a newspaper can be bought regularly for less than the cost of the paper on which it is printed. Possibly the secret of many newspaper evils lies in the fact that the advertisers and the readers can be played off against each other. In order to get a large circulation with which to catch advertisements, the price of the paper is reduced, its size increased, its headlines made sensational, and illustrations introduced to stimulate the flagging senses of the reader. Then, as advertisements flow in at increased rates, the price of the paper can be further reduced and its attractions multiplied. Under these circumstances advertisements of doubtful character are accepted as a matter of course. Ought not the advertising sheet and the newspaper be separated so that each would have to pay for itself? Advertisements that are really of general interest to the public should, on such a theory, be published as news. At any rate, the chief argument against the endowment of a newspaper seems to rest on a misconception of present conditions, and there is no apparently satisfactory reason why some of our surplus millionaires should not emulate the example of Mr. Hearst, with this difference, that they devote their money, their brains, and their energy to the promotion of public intelligence instead of the stimulation of public passion. In the meantime it may be possible to work toward a better journalism by introducing or strengthening the legal responsibility of newspapers for publishing only reliable news.

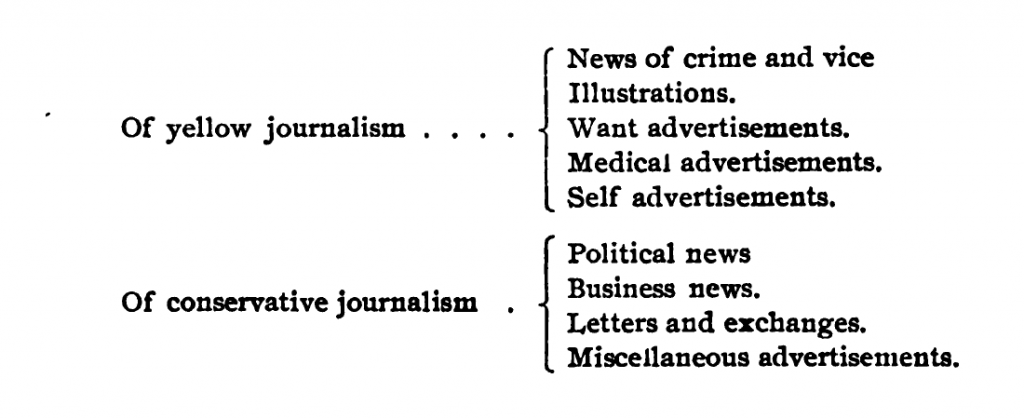

It is readily apparent that part of the reason why the author disdains advertising is due to how William Randolph Hearst ran his newspapers, but I'll get to that another day. But here is the answer. The endowment of yellow journalism is advertising. That is, running it like a business. There is a very interesting graph on page 77 which illustrates this:

Notice how he puts nearly all advertisements into the "yellow journalism" category? Despite this book being written in 1900, 113 years ago, I am confident that this view is still widely held. Perhaps even more widespread today than it was back then.

What else does this writer believe which will shed light upon this view? See page 89:

If we blame the "public" solely, there is no apparent remedy; for the newspapers themselves are coming more and more to be the principal organs through which public tastes are formed and appeals to public intelligence made. The tool is master of the man, and, too late, we blame the man. It is certainly probable that a newspaper directly responsible to an intelligent and conscientious public would have to be a good journal in order to succeed. In a perfect democracy the newspaper business would regulate itself. But, unfortunately, the "public" is not altogether intelligent and conscientious, and for that reason the newspaper becomes an organ of dynamic education. It would be treachery to social ideals for schoolteachers to choose and pursue their profession simply as a money-getting enterprise. The same is true of journalism. Responsibility must attach to this public function.

Do you find it interesting how seemingly all of these old progressive-era writings consider the newspaper as a way to control the masses? I know I do.

If the people trusted their chosen governors and were themselves united in their support of the public welfare, they would undoubtedly be willing to put the newspaper business, like education, into government hands, though not as a monopoly. In fact, however, we as a people still regard government as a necessary evil. It is my belief that the salvation of our cities depends on the displacement of this view by the view that government, the co-operative organization of all for the benefit of all, is a necessary good.

This writer does not like the fact that most Americans(in 1900) viewed government as a necessary evil, he would prefer people to love government. But I think this one speaks the loudest, page 86:

The newspaper, which is preeminently a public and not a private institution, the principal organ of society for distributing what we may call working information, ought not to be controlled by irresponsible individuality.

That really sums it all up. First, "irresponsible individuality", that's all progressivism. They're largely collectivists. But further, is this faulty idea that newspapers are public institutions.

All disagreements with the author aside, this is what they believe as journalists. Institutionally, journalism is an activist profession.

http://tinyurl.com/kvhcnhg