W. Randolph Hearst

This is the highest and most profitable knowledge, truly to know and to despise ourselves. To have no opinion of ourselves and to think always well and highly of others, is great wisdom and perfection. If thou shouldest see another sin openly or commit some grievous crime, yet thou oughtest not to esteem thyself better; because thou knowest not how long thou mayest be able to remain in a good state. We are all frail; but as to thee, do not think they are more frail than thyself. - Thomas a Kempis, Book I. Ch. I.

I.- AN INTRODUCTORY HOMILY.

THE hero of the month is unquestionably Mr. William Randolph Hearst. When Mr. Hearst was campaigning two years ago for the Governorship of New York State, in a village beyond Albany Mr. Hearst's automobile met a coal wagon. The driver, a big, burly fellow, with his hands as black as his face, leaned over and gripped Mr. Hearst's fingers and shouted, " Good boy ! To hell with the Coal Trust, Willie!"

" To-Hell-with-the-Trusts-Willie!" is a name that may yet become as famous in history as that of the famous Praise-God-Barebones of the English Commonwealth. For last month Willie Hearst has indeed - to borrow the picturesque but profane vocabulary of the West - been giving the Trusts hell all round. And not the Trusts only. The politicians who have blackmailed the Trusts, and the political leaders who became the hirelings of the Trusts, have all received their medicine. Republican and Democrat alike have had it meted out to them fiery hot, while all the world has wondered, and not a few of its denizens have lifted up holy hands of unctuous righteousness and have thanked God they were not sinners like other men, and especially not like these (re)publicans across the Atlantic.

Now if the saints of all creeds may be believed, there is no sin so dangerous and deadly as self-righteousness. The harlot precedes the Pharisee into the kingdom of heaven. And therefore before entering upon the description of Mr. Hearst's remarkable personality, let me administer to John Bull a little salutary physic in order that he may attain to what Thomas a Kempis calls " the highest and most profitable knowledge truly to know and to despise ourselves."

By a providential good fortune, if we look at it from the point of view of Thomas a Kempis, in the same week that Mr. Hearst began to explode his bombshells in the headquarters of the Republicans and the Democrats of the United States, the Director of Public Prosecutions unfolded in the Thames Police Court a story of corruption - on a small scale, it is true - which in its way is quite as bad as anything Mr. Hearst has brought to light in America. As Poplar is to the United States, so is the dishonesty unveiled at the Thames Police Court to the revelations of Mr. Hearst. The case is not yet decided, and it is impossible to discuss the truth or falsehood of the charges against the individuals who have been placed in the dock, from which everyone hopes they may issue " without a stain upon their characters." But the main outlines of the story, told by the chief offender, who has turned King's evidence, can be stated without offence. This man, " a builder named Calcutt," accuses himself of having secured a series of contracts, chiefly for work done on the Blackwall Branch Asylum, covering the years 1903-6, by the simple process of bribing eight members of the Board of Managers, who gave him a series of fat jobs, amounting in all to about £3,000. The law requiring that all contracts exceeding £50 should be let by public tender was ingeniously evaded by splitting a contract for one building into a series of separate contracts for each room. The official prosecutor said it was impossible to explain what this Board did in any other way than according to the story of Calcutt. It was a story of bribery and corruption, of gifts of clothes, coals, presents, drinks, and work.

The case of Calcutt was but one of many others. When a tea contract was to be disposed of, one of the members exclaimed, " If he gets that contract, I want £10." He got that £10. When public money was spent on these lines, it is not surprising that the expenditure of this particular Board went up by leaps and bounds. In 1901 it was £35,000 a year; in 1906 it had risen to £62,000. A public outcry having been made, the expenditure has since been reduced by £10,000. It is, perhaps, not altogether without justification if we take it that this single local board, elected from and by two local Boards of Guardians in one East End district, entailed upon the ratepayers an expenditure of £10,000 a year as a result of the methods of jobbery exposed at the Thames Police Court. If this Board stood alone we might think less of it. But does it stand alone? If a searching probe were applied to all our local governing bodies, as it has been applied in Poplar, how many would escape scatheless ? Only a month or two ago, after a long and exhaustive trial, a batch of East End guardians were sent to gaol as criminals for similar malpractices. "Think ye that those upon whom the Tower of Siloam fell were sinners above all the rest of the Galileans? I tell you nay." So I quote these instances of corruption in the East End to point the moral and illustrate the warning of Thomas a Kempis : "If thou shouldest see another sin openly or commit some grievous crime, yet thou oughtest not to esteem thyself better, because thou knowest not how long thou mayest be able to remain in a good state."

It will be replied that the misdeeds of the East End may be set off against the misdeeds of Tammany Hall and the corrupt City Governments of America. But the exposures made by Mr. Hearst are much more serious, inasmuch as they impugn the honour of the leaders of the parties to which are entrusted the government of tie nation. Granted. But this compels me to point to another skeleton in our closet. The charges of Mr. Hearst, reduced to their essence, amount to this, that both parties when elections came round levied contributions from the Trusts. He supplemented this by imputing specific acts of corruption in the purchase of individual members of the legislature, but these may be ignored for the present. The chief charge, the only one which indirectly affects Mr. Roosevelt, is the fact that the party managers on the eve of an election levied contributions for campaign funds from the great business combinations' called Trusts. In return for such contributions they hoped to be insured against interference, or, in their own phrase, they were "guaranteed a Conservative Administration."

This, of course, is scandalous and worthy of all reprobation. But those who live in glass houses should not throw stones. If we had a Mr. Hearst in this country, and our law of libel was as elastic as that of America, does anyone think that the world would not be scandalised by revelations as to corruption in high places in Westminster as well as in Washington? The English variety of corruption differs from that which flourishes across the Atlantic as a monarchy differs from a republic. It has often been cynically declared that the one permanent advantage a monarchy possesses over a republic is that under one you can bribe respectably with honours, whereas under the other you must pay down in hard cash.

I do not want to bring railing accusations against either of our political parties, for both are equally guilty or equally innocent. But if anyone imagines that the electoral expenses fund of either Liberal or Conservative party is not constantly replenished by what in blunt Saxon may be called the sale of honours and titles, he must be a very innocent. It is all done "on the sly." No price list is exhibited in the windows of the Government whip: "Knighthoods cheap to-day, guaranteed at £5,000. Baronetcies from £25,000 and upwards. Peerages £50,000 down," because that would create a scandal. But if any wealthy man wishes to secure a handle to his name, he will soon discover that there is no surer and shorter road to the fount of honour than by a liberal subscription to the party funds. If this be not so, why should there be so insurmountable an objection on both sides to enacting that whenever any title or rank is conferred by the Crown, a message should be sent to Parliament stating for what cause the King delighteth to honour these particular lieges ? Those anxious to investigate this obscure subject will do well to make application to Mr. Henniker Heaton, the incorruptible one who twice refused a baronetcy offered him in recognition of his services to the State, on the ground that he did not care to accept a title which was usually bestowed in return for cash down.

All of which is a homily to my British readers not to think of themselves more highly than they ought to think, and when reading the story of W. Randolph Hearst and his revelations let them remember the parable of the mote and the beam, and take to heart with all humility the warning, Let him who thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall.

II.- W. RANDOLPH HEARST.

When I returned from my last visit to America in 1907 I wrote in the REVIEW OF REVIEWS for December, "For tie last ten years I have never varied in stating that from my own personal knowledge of the man, insight into his character, and knowledge of his capacity, Mr. Hearst has it in him to be the great personal power in America for the next twenty years. He may wreck everything, but on the other hand, he may be in the future, as he ha been already in the past, a force making for progress and for the diminution of many abuses. Mr. Hearst may be a good man or he may be a bad man - that is a question of comparison as to which side the balance lies in a strangely complex character - but that he is a great man, and with a great strain of goodness in him, I have no doubt whatever."

In a previous number of this magazine I expressed my conviction "that the character Mr. Hearst is the unknown x in the future of American politics. The owner of the New York American and half-a-dozen other journals is for weal or for woe the factor which will exercise more influence on the history of the United States for the next twenty years than any other, not even excepting Mr. Roosevelt himself. No mistake can be greater than to imagine that he is un quantite negligeable. Not twelve months have passed since this was published, and already everyone is in amaze at the way in which Mr. Hearst has in a single week succeeded in dominating the political situation in America on the eve of a Presidential election.

Who is this "To Hell-with-the-Trusts Willie Hearst"?

The facts of his meteoric career are soon told. He is the son of the great millionaire mineowner, of California, Senator Hearst, whose wife, Phoebe, still survives. He was born in 1864. He was sent up to Harvard by his parents, and he was sent down from Harvard by the University authorities. After returning to San Francisco he fell in love with a well-known and beautiful actress of a good Californian family, but his people, regarding it as a mesalliance, prevented the marriage. Thereupon young Hearst, following the Byronic example, sought to find in many what he had failed to find in one, and set about painting the town red in approved libertine fashion. From that dates the period of his career, which was brought to an end half-a-dozen years ago by his marriage. In the midst of his scandalous debauchery he suddenly surprised his father by announcing a desire to go into journalism. " Don't be a mere tag on a money-bag," said a friend to the young Hearst. Old Senator Hearst sniffed a bit at the idea of Willie making out as an editor, but he made over to him the San Francisco Examiner.

To the amazement of his parents and the dismay of his friends, it was soon discovered that when they had started Willie Hearst in journalism they had let

loose an earthquake on the Pacific Coast. Mr. Sydney Brooks, who wrote a very well-informed article on " The Significance of Mr. Hearst" in the Fortnightly

Review last December, says:-

He determined to be the Pulitzer of the Pacific Coast, and to conduct the Examiner with the keyhole for a point of view, sensationalism for a policy, crime, scandal, and personalities for a speciality, all vested interests for a punching bag, cartoons, illustrations, and comic supplements for embellishments, and circulation for an object. He entirely succeeded. His father bore the initial expenses, and in return had the gratification of finding the Examiner turned loose among the businesses, characters, and private lives of his friends and associates. Hardly a prominent family escaped; the corporations were flayed, the plutocracy mercilessly ridiculed, and the social life of San Francisco, and especially of its wealthier citizens, was flooded with all the publicity that huge and flaming headlines and cohorts of reportorial eavesdroppers could give it. San Francisco was horrified, but it bought the Examiner; Senator Hearst remonstrated with his son, and to the last never quite reconciled himself to the "new journalism," but he did not withhold supplies, and in a very few years the enterprise was beyond need of his assistance and earning a handsome profit.

When he was turned thirty he conceived the idea of duplicating in New York the success he had achieved in San Francisco. Mr. Pulitzer, of the New York World, was in possession of the field. But Mr. Hearst had received a million sterling from his mother, to whom Senator Hearst had left his fortune, and he flung himself into the combat with the fine frenzy of a journalistic genius who had money to burn and a whole continent as a battlefield. He bought up Pulitzer's best men, and when they did not stay bought, but went back to Pulitzer at increased salaries, Mr. Hearst bought them a second time at prices with which even Mr. Pulitzer could not compete. In a very few years, by lavish expenditure, audacious enterprise, and unstinted sensationalism he had secured for the New York Journal the first place in circulation in the United States.

It was just when Mr. Hearst had succeeded in achieving his ambition to secure circulation that I made his acquaintance. It was in the fall of 1897. I had crossed the Atlantic with another remarkable product of American life - Richard Croker, of Tammany Hall - and I was most anxious to make the acquaintance of Mr. Hearst. I went down to his office shortly before midnight. I found the young millionaire in his shirt-sleeves busily engaged in preparing next day's paper. As soon as he was through the press of his work he sat down, and I had one of the most memorable conversations of my life. It takes rank with my interview with Cecil Rhodes when he told me he wished to make me his heir, and my interview with Alexander III. when I discovered him to be the Peace-keeper of Europe, as among those which are indelibly impressed on my memory. Mr. Hearst looked at me somewhat quizzically as he sat down and bade me welcome.

Plunging at once in medias res, I said:-

" Mr. Hearst, I am very glad to see you. I have been very curious to see you for some time, ever since I saw how you were handling the Journal. But do you know why I want to see you?"

Mr. Hearst smiled and said he thought it was a great compliment.

"Not at all," I went on. " I want to see you because I want to find out if you have got a soul. Listen to me," I said; "I have been long on the look out for a man to appear who will carry out my ideal of government by journalism. I am certain that such a man will come to the front some day, and I wonder if you are to be that man. You have many of the qualities such a man must possess. You have youth, energy, great journalistic flaire, adequate capital, boundless ambition - yes, you have all these. But - but, I am not sure you have got a soul, and if you have not a soul all the other things are as nothing."

"What do you mean?" said Mr. Hearst. "What do you mean by having a soul?"

"Have you ever read Lowell's 'Biglow Papers'? Do you remember ever having read the prose preface to 'The Pious Editor's Creed'?"

"Promise me," I said, "that you will hunt out the book and read it before you go to bed this night. I read it before I was twenty, and it has dominated ever since my conception of journalism. Read it and you will see what I mean by asking whether you have got a soul. Lowell's conception of journalism-"

"Oh," said Mr. Hearst with a sneer, "journalism is only a business, like everything else!"

"There's just where you make your mistake," I retorted vehemently. " Journalism is not a business just like everything else, and it is because you think it is so, and act on your belief, that I doubted whether you had found your soul. Journalism," I went on, "is the heir of all "the theocracies, monarchies, aristocracies, hierarchies, plutocracies. In a democracy the journalist is the one man whose voice is heard day by day by all the people. He has all the opportunities, all the responsibilities. It is his mission, as Lowell said, to be the Moses of Humanity, leading each generation across that wilderness of sin called the Progress of Civilisation."

"It's all very well for you to talk like that," said Mr. Hearst, "because you have made your mark and you have a right to be heard. But if I were to start on to the prophet business, why, people would say, 'Who is this young fellow who's talking to us like that? Guess he's pretty considerable swell-headed!'"

"My dear Mr. Hearst," I answered, "if I had waited till I had made my mark before starting in the prophet business I never should have made my mark. Do you know," I asked, "what the New York Journal looks like to me every time I take it up?"

"No," he replied. " I'm rather interested to hear."

"This," said I. "It seems to me exactly like a first-class Atlantic liner, fitted up with the latest improvements, with the best machinery, a first-class crew, a crowded complement of passengers, which, when it has got out of sight of land, is discovered to have neither pilot, nor chart, nor compass on board. So it goes steaming ahead, now this way, now that, without an aim, without an object, except only to show her speed."

"Well," said Mr. Hearst, "there is something in that, I admit. But what would you have me do with it? Where should I sail to?"

"If you do not know yourself what is the best course to steer, then consult the best Americans who think about the public welfare. Cecil Rhodes used to say that there were not more men in England who were worth consulting about the Empire than you can count on the fingers of two hands. That was too low an estimate. Suppose we say that there are twenty-five such on an average in every State in the Union. That gives you 1,000 men whose judgment is the best. Make it your business to know the whole 1,000, and condense from the total mass of their contributions what you find to be the common denominator of their ideas. Make that your message. Use your paper to give more power to the elbow of all the best and wisest citizens. Be their organ, their mouthpiece, make your paper their sceptre. And if you do, there is no man living in the United States who will have such an influence for good for so many years as you will have. Presidents last eight years at the most. You will never go out of office. But it all depends," I said, "whether you've got a soul, and that is why I've come here to-night to find out."

"It's very interesting what you say," replied Mr. Hearst. " It never occurred to me in that light before."

"Don't think it will be an easy road," I went on. "It is not a path of roses by any means. It may land you in gaol, or it may lead you to the scaffold; but a man with a soul within him counts these things as but trifles compared with the opportunity of wielding such influence over millions of his fellow-men."

We had a good deal more talk, but the above was the gist of it. I left after midnight, marvelling a little at the unwonted liberty of utterance which had been given to me with this total stranger, and wondering not a little as to what impression my unceremonious discourse had made upon the mind of Mr. Hearst.

After I returned home and was settling down to work I was startled by receiving every now and then from Mr. Hearst cablegrams addressed to his London correspondent asking him to obtain and to telegraph what I thought upon what the Journal was doing in this, that, or the other direction. I do not for a moment argue post hoc propter hoc, but it was almost immediately after that midnight talk that Mr. Hearst began to realise the ideal of a journalism that does things. He took up the question of municipal ownership. He engaged Arthur Brisbane, the son of Brisbane the Fourierist, to write editorials. He began the battle against the Trusts; he made the Spanish-American war. For weal or for woe Mr. Hearst had found his soul; for weal or for woe he had discovered his chart and engaged his pilot, and from that day to this he has steered a straight course, with no more tackings than were necessary to avoid the fury of the storm. Some years afterwards I met Mr. Hearst in Paris. He recalled our first conversation, and said, " I never had a talk with anyone which made so deep a dint in life."

The acquaintance thus begun has continued unbroken down to the present time. I am afraid I incurred no small amount of odium by contributing to the Journal in its early days, and last year when I was asked to describe the Peace Conference for the American (the Journal was rechristened American after a few years), I was warned by my friends that nothing would so hopelessly discredit me as to figure in the pages of that "Yellow Journal." Mr. Roosevelt's opinion of Mr. Hearst, as he delivered it to one of Mr. Hearst's own interviewers, and repeated it to me, was quite unfit for publication - anyhow, it was not published. But what was to be done? In 1899, when the first Peace Conference met at the Hague, it was Mr. Hearst and Mr. Hearst's syndicated papers which alone were willing to pay for cabling 2,000 words every Sunday of what had been done at the Hague the previous seven days. Last year they undertook to do the same, but as public interest waned they did not continue their publication.

I saw Mr. Hearst last year just before I left New York, the day after he had published a scathing attack upon the Democratic party organisation, in which the curious will find a foreshadowing of the smashing blow which last month drove Mr. Bryan to get rid of the Treasurer of his party. We had quite a long talk. I have probably talked with as many varieties of notable men as any of my contemporaries. I put Mr. Hearst very high in my graded categories of remarkable men. A cooler hand and a steadier head few men have. He discussed with almost Olympian impartiality the probabilities of American politics, the characters of American public men. He seemed to be singularly free from bitterness. He said he thought the Republicans could not help carrying the next Presidential Election even if they tried. Roosevelt's influence would be sufficient to carry any ticket. As to Mr. Bryan's chances, he spoke kindly of Mr. Bryan, but he utterly despaired of the Democratic party machine being capable of grappling with the Trusts. It had chopped and changed too much to command the confidence of the country, and the personnel of its organisation was utterly bad.

I asked him why he had not adhered to the career which, ten years before, I had said would lead him to a position in the Republic much more influential than that of President. "Oh," he replied, "I was tired of telling people what they ought to do: I wanted to see if I could not do things myself. But that is over now. I am not, going to stand again for Presidency."

"But," I objected, "you stood for the Mayoralty of New York and then for the Governorship of the State."

"I did not want to stand for either," he replied. "The boys fairly forced me into the Mayoral contest. They said that it was no use my rallying them to the fight if I would not do my share in the battle. I refused and refused, and it was only when it was quite clear that the whole party would be ruined if I did not give in that I consented to stand."

"And were not elected?"

"Oh, I was elected right enough. Legally and rightfully I am Mayor of New York at this moment. But they deliberately falsified the election returns. If we could have had an honest count of all the ballots cast I should have been in the City Hall at this moment."

"But the Governorship?"

"Oh, that was a corollary of the cheating that seated the candidate of the minority in the Mayor's chair. Our fellows were mad at that scandalous swindle, and they nominated me for Governor."

"Out of which you were kept by Mr. Root's letter from Roosevelt?"

"Oh, no ; not at all. I don't think that letter materially affected the result. What did affect the election was the fact that as the Republicans had usurped the mayoralty, they were able to swing the whole of the civic employees' votes for Mr. Hughes. If they had not been in possession of the mayoralty, or if they had remained neutral, most of these employees would have voted for me, as they did when I stood for Mayor."

Mr. Hearst spoke without acrimony, with a good deal of philosophical cynicism. But it was quite clear to me that he could not be counted upon as a factor to secure the success of Mr. Bryan.

My own impression of Mr. Hearst has never varied. He is one of the ablest men in America, the keenest and most capable journalist in the world. Whatever

his past may have been in the days when he was Madcap Hal, he has put away the vices of his hot youth and is now, like Henry V., the very opposite of his former self. The danger of course is that there may be a taint, a certain moral deterioration born of the period of his libertine youth which may deaden the moral instinct of the maturer man. As I used to say of Rhodes that his ethical education had been neglected, I would say of Mr. Hearst that his ethical perception may have been dulled by the riotous life of his earlier manhood.

The fine sense that instinctively recoils from anything that is not chivalrous or noble seldom survives a prolonged mud-bath in which the man wallows together with the dragons of the primeval slime. Hence certain things in his journals which make his friends uneasy and cause his enemies to blaspheme. There is a certain coarseness of invective, more worthy of a bargee than of a gentleman, in which Mr. Hearst occasionally revels. But when all deductions are made and all discounts allowed for, Mr. Hearst is to-day probably the most typical American of the new generation.

If you want to know the kind of man Mr. Hearst is, it is absurd to go ransacking Roman history to find his prototype. To some he is a reincarnation of the famous brothers Gracchi, to others he is the modern Catiline. It is much simpler, and the ordinary reader will understand much better what he is if I say that he is Alfred Harmsworth and W. T. Stead rolled into one and reincarnated in the body of an American of the Pacific Coast. He has the qualities of both the editors of the Daily Mail and of the Review of Reviews - although it is probable that the proportion of Stead is less than the proportion of Northcliffe. But he is like me in being a propagandist and a hot gospeller, which Lord Northcliffe is not, and never can be. It is not in him. But he has all Lord Northcliffe's qualities - his journalistic flaire, his skill in choosing willing slaves, his insatiable ambition, and his great business capacity.

His appearance has been recently described by two close observers. Mr. Arthur Brisbane says:-

He is a big man. He is more than six feet two in height, very broad, with big hands and big feet, a strong neck that will stand up for a long time under a heavy load. His hair is light in colour, and his eyes blue-gray, with a singular capacity for concentration. His dress of late has been the usual uniform of American statesmanship, combining the long-tailed frock coat and the cowboy's soft slouch hat.

Here is a companion picture by Mr. Sydney Brooks:-

In dress, appearance, and manner he is impeccably quiet, measured, and decorous. He struck me as a man of power and a man of sense, with a certain dry wit about him, and a pleasantly detached and impersonal way of speaking. He stands six feet two in height, is broad-shouldered, deep of chest, huge-fisted, deliberate, but assured in all his movements. But for an excess of paleness and smoothness in his skin one might take him for an athlete. He does not look his forty-four years. The face has indubitable strength. The long and powerful jaw and the lines round his firmly clenched mouth tell of a capacity for long concentration, and the eyes, large, steady, and luminously blue, emphasise by their directness the effect of resolution. In more ways than his quiet voice and unhurried, considering air, Mr. Hearst is somewhat of a surprise. He neither smokes nor drinks; he never speculates; he sold the racehorses he inherited from his father, and is never seen on a race track; yachting, dancing, cards, the Newport life, have not the smallest attraction for him; for a multi-millionaire he has scarcely any friends among the rich, and to "Society" he is wholly indifferent; he lives in an unpretentious house in an unfashionable quarter, and outside his family, his politics, and his papers, appears to have no interests whatever.

Many people used to say that Mr. Hearst was a cypher, that he would be nothing without Mr. Brisbane, etc. The fact is, Mr. Hearst is anything but a cypher. In the expressive Americanism it is Mr. Hearst who is "it," and no one else but Mr. Hearst. He has not a resonant voice, but he is an effective speaker. He is as slashing a writer as any of those wielding a pen on the American Press.

The question of questions that is asked me always about Mr. Hearst is this: "Is he sincere?" If I were put in the witness stand and made to answer that question on my oath I should say, "To the best of my knowledge and belief he is." That he is absolutely free from self-seeking I do not for a moment contend. He is no Pharisee. He is a man avid of success, measured by increase of circulation and increase of influence; an ambitious man as Napoleon was ambitious, and with something perhaps of the unscrupulosity of the great little Corsican. But in the inmost soul of him - and he has a soul and has found it - there is a desire to serve the common people. He is a Jeffersonian Democrat, a natural demagogue, and a man who is proud of being the tribune of the people.

It may be said if Mr. Hearst be so, why then this and that? Mr. Hearst is a man of action, a journalist engineer to whom nothing is sacred, a man whose balance-wheel of moral principle is not dominant, a kind of American Jesuit to whom the end justifies the means. But this brings me to my next chapter.

III.- THE HEARST NEWSPAPERS.

Mr. Hearst is the owner of nine distinct newspapers published in five cities in the United States and three widely circulated magazines, all of which pay. To quote Mr. Brisbane:-

He has built his newspapers up to a daily circulation of two millions. And that circulation is increasing constantly. Every day Hearst is able to talk with two million American families scattered everywhere in this country. His newspapers arc published in Boston, New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles. And they will soon be published in many other cities. His voice reaches farther than the voice of any other man in the country. There has never before been assembled in this world an audience such as that which Hearst commands, and therefore it is safe to say that there has never been a man possessing his peculiar influence and power for good.

According to Mr. Creelman, Mr. Hearst, up to 1906, had invested £2,400,000 in his newspaper business, and every year he spends £3,000,000 in producing his various publications. This daily outlay of £8,000 purchases 400 tons of white paper, which are converted into two million newspapers varying from eight to thirty or forty pages, pays the wages of 4,000 regular employees, and the lineage of 15,000 correspondents writing in space. He bought the New York Journal for £30,000, and has now sunk £1,600,000 in that property.

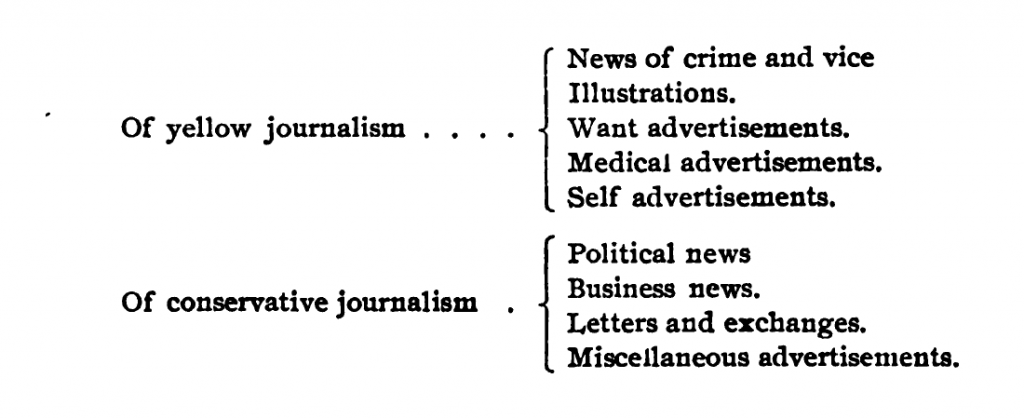

All of his papers are papers that appeal to the million. They are printed for the million and are read by the million. They are sensational and abusive, but not, so far as I have been able to discover, obscene or filthy. Mr. Hearst, indeed, gibbeted James Gordon Bennett for publishing indecent advertisements in the Herald, and obtained a judgment against him. He was accused by President Roosevelt of having incited by his violent attacks the assassination of President McKinley, and there is no variety of abusive epithet that has not been heaped upon him and his paper. But it takes all sorts of people to make a world, and it takes all sorts of papers to minister to the tastes of all sorts of people. Full reports of murder cases are not always edifying reading, but with the memory of the Luard murder and suicide still fresh in our memory it does not do for English journalists to give themselves airs. That Mr. Hearst plays to his gallery is true, and he would not deny it, for it is by the support of his readers he lives. That he would, other things being equal, prefer to produce more respectable papers I believe, but he caters to his public, as do many more pharisaic journalists who happen to have a less cosmopolitan public than that to which Mr. Hearst appeals.

Mr. Hearst talked good sound peace talk when I was last in New York, and the editorials in the American would have delighted the heart of Dr. Darby of the Peace Society. But if any man made the war with Spain inevitable it was Mr. Hearst, just as it was Lord Northcliffe who largely contributed to bring about the war with the Boers. Appealing as he does largely to the Russian Jews of the Ghetto, to the Germans, to the Irish, and to the non-English conglomerate, he is constantly under the temptation to twist the lion's tail. His late outburst in the Times exhibited him at his worst. I have a great belief in Mr. Hearst, and a great affection for him, but I am afraid I must admit that the influence of his papers would not tend toward peace and sweet reasonableness in the conduct of the foreign affairs of the United States.

Mr. Brisbane boldly claims for Mr. Hearst that -

he has made dishonest wealth disreputable throughout the nation. He is the greatest awakener and director of public opinion and public anger against injustice that the country has seen for many years.

Hearst has made innumerable fights in the interest of the people at his own expense, with great expenditure of money and of personal energy. Various trusts have been fought by him through the courts and up to the Supreme Court. He certainly has the honour of being hated more deeply by the public enemies of this country than any other man in it. A mere enumeration of the lawsuits that he has begun and prosecuted on behalf of the public welfare fills out a considerable pamphlet.

A more impartial witness, writing in Collier's Weekly, says:-

It is due to Mr. Hearst, more than to any other one man, that the Central and Union Pacific Railroads paid the £24,000,000 they owed the Government. Mr. Hearst secured a model Children's Hospital for San Francisco, and he built the Greek Theatre of the University of California - one of the most successful classic reproductions in America. Eight years ago, and again this year, his energetic campaigns did a large part of the work of keeping the Ice Trust within bounds in New York. His industrious Law Department put some fetters on the Coal Trust. He did much of the work of defeating the Ramapo plot, by which New York would have been saddled with a charge of £40,000,000 for water. To the industry and pertinacity of his lawyers New Yorkers owe their ability to get gas for eighty cents a thousand feet, as the law directs, instead of a dollar. In maintaining a legal department, which plunges into the limelight with injunctions and mandamuses when corporations are caught trying to sneak under or around a law, he has rendered a service which has been worth millions of dollars to the public.

Verily a newspaper man, who uses his newspapers to do things.

One of the things which weigh most in Mr. Hearst's favour is the extent to which he commands the devoted service of some of the ablest journalists in America. It is true he pays them well. Mr. Brisbane receives £10,000, the salary of the President of America; the next best-paid member of his staff receives £8,000; the third, £6,000. Five assistants receive £5,000 each. But no salary, however high, could command the unstinted enthusiasm with which Mr. Brisbane serves Mr. Hearst. He declares:-

Hearst represents unselfishness in public life. In need of nothing personally, he is not satisfied while others fail to thrive as they should in a country such as this. He is ambitious, without personal conceit. He is extremely tenacious. He is absolutely temperate, free from fondness for dissipation of any kind.

The following are the names of the leading members of his staff as they were given by Mr. Creelman two years ago:-

Solomon Solis Carvalho, general manager of all the Hearst newspapers; a highly trained journalist and shrewd business man of Portuguese descent.

Arthur Brisbane, editor of the New York Evening Journal and writer of its remarkable editorials. He is the son of Albert Brisbane, disciple of Fourier, the French socialist.

Samuel S. Chamberlain, managing editor of the New York American and supervising editor of all the Hearst newspapers, was for many years the friend and secretary of James Gordon Bennett.

Morrill Goddard, editor of the New York American Sunday Magazine.

Max F. Ihmsen, Mr. Hearst's political manager; once a member of the New York Herald's staff.

Clarence Shearn, Mr. Hearst's lawyer and the thinker-out of his costly injunction suits and other litigations against corporations and "oppressors of the common people."

Mr. Hearst is a millionaire, a multi-millionaire. Besides his newspapers he owns a million acres of land. But as it was with Rhodes, money is to him only a means to power. He spends money like water in the political education of the people. He was reputed to have spent £200,000 on the gubernatorial election in 1906, but even if he only spent the £51,274, which he returned in compliance with the election law, it was a large sum. He does not need to bleed the Standard Oil for his campaign funds; he bleeds himself.

When Mr. Hearst was in London five years ago he was interviewed upon his conception of journalism. He replied in terms which sound something like a far-away echo of the harangue I hurled at him six years before in his New York office.

"'Yellow journalism,'" said Mr. Hearst, "is active journalism. It is the journalism which is not content with merely printing news, not content with merely securing an audience, but which seeks rather to educate and influence its audience, and through it to accomplish something for the benefit of the community and the whole country. My particular form of yellow journalism attacks special privilege and class distinction, and all things that I believe to be undemocratic and un-American. A journalism which employs the power of its vast audience to accomplish beneficial results for all the people is the Journalism of the Future. Better still, I think it is the Journalism of the Present. I cannot imagine why anyone should want to print a newspaper except for that purpose. I myself don't find any satisfaction in sensational news, comic supplements, dress patterns, and other features of journalism, except as they serve to attract an audience to whom the editorials in my newspapers are addressed. You must first get your congregation before you can preach to it, and educate it to an appreciation and practice of the higher ideals of life."

There was some talk once of Mr. Hearst, after stringing newspapers across the Western Continent, establishing a Hearst organ in London. He made soundings, but he abandoned the project.

"Why?" I asked.

"Because," he replied dryly, with a humorous twinkle in his eye, "I fear that the law of libel in the old country is too strict to allow legitimate scope for newspaper enterprise."

IV.- HIS DISCLOSURES.

Mr. Hearst at one time was a Democrat who took the stump for the Democratic party. He was elected to Congress on the Democratic ticket, but made no mark in the legislature. He is a personal friend and has been a staunch supporter of Mr. Bryan, but he has just dealt him, through his organisation, one of the hardest of knocks. At one time he believed that the Democratic party could be used against the Trusts. He has always been opposed to the Republicans for the cause succinctly stated by him in his early Democratic days:-

I do sincerely believe that the Republican party as a political institution is so much indebted to the Trusts, is under so many obligations to the Trusts, that it will never legislate against the Trusts, nor even enforce against them the laws which already exist.

The Trusts have received so many privileges from the Republican party, and the Republican party in return has received so many favours from the Trusts, that a bond has grown between them, uniting them like the Siamese twins, and you cannot stick a pin in the Trusts without hearing a shriek from the Republican party ; and you cannot stick a pin in the Republican party without hearing a roar from the Trusts.

Now, you can't expect one Siamese twin to turn against his Siamese brother, and you cannot expect the Republican party to turn against the Trusts. The Republicans may say they will - they frequently do say they will. But they never do it.

In his campaign two years ago for the Governorship of New York State he made things hum by the aid of gramophones, pyrotechnics, picture posters, choral societies. An observer describing the election said:-

All last week there were constant Hearst processions, with red fire, sky-rockets, and illuminated banners, in every town and village in the State. Thousands of phonographs were utilised in this campaign of vituperation, and every town was fully supplied with machine-made oratory.

Tens of thousands of copies of the Hearst newspapers were distributed free nightly picturing Mr. Hughes and other prominent Republicans as rats and other loathsome animals.

The Hearst posters showed babies poisoned by bad milk, mothers freezing to death on Christmas Day at the door of a trust millionaire, with dead children at their feet; corporation magnates laughing, with their heels in working men's faces; and others murdering the "common people" with tramcars and motor-cars.

The vicissitudes of the "common people," represented by a meek little dwarf, and the antics of the steel, ice, coal, railway, and other trusts, represented by men of unusual size, have furnished much amusement in the east side slums, where pictures are more valuable as vote winners than speeches.

His intervention in this Presidential Election reminds me somewhat of the sensation produced in London in 1885 by the publication by the Pall Mall Gazette of "The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon." Everyone knew that these horrors had existed. But no one knew exactly how or by whom the hateful traffic was organised. When the Pall Mall began its revelations there was for a time a sickening sense of terror among the more highly-placed roues, for no one knew whose names might be revealed before the publication ceased. The Pall Mall Gazette, however, held its hand. Its object being to pass a new law, and not to pillory individuals, there was no need to mention names. But Mr. Hearst has mentioned names. Everyone knew that both parties blackmailed the trusts and were in turn subservient to them; but to know that criminality exists is one thing, to be able to pin it down to the counter is another. Mr, Hearst has nailed it down to the counter.

There is no need to enter into the disclosures in detail. The main outlines are all that non-American readers care for. What Mr. Hearst did was to publish letters - presumably stolen - which, in the opinion of the American public, from Mr. Roosevelt downwards, proved that certain notable political chiefs had been tampered with by the Trusts. Senator Foraker was the chief Republican victim. He is a senator whose position in the Republican party somewhat resembled that of Mr. Chamberlain under Mr. Gladstone - that is to say, he is a great political personality, often insubordinate and sometimes hostile to the Administration, whom it was, nevertheless, very necessary to keep in line for the Presidential campaign. Mr. Hearst published his incriminating letters, and Senator Foraker dropped like a shot pheasant. Mr. Haskell, Governor of Oklahoma, Mr. Bryan's friend and the trusted treasurer of the party, was the chief Democratic victim. He made a show of fight, but Mr. Bryan had to fling him overboard like another Jonah. Poor Mr. Haskell, the Poet Laureate of the Anti-Trust campaign, had written campaign songs for his party breathing vengeance against the Trusts.

And now, like Actaeon, he was torn to pieces by his own dogs. There were others of less note. There is a letter from Mr. Sibley advising the Standard Oil Trust to invest £200 in a loan to a senator " who is one who could do anything in the world that is right for his friends if needed." Senator McLaurin, a Democrat, is shown to have been in close business relations with the Standard Oil people, and so forth.

But President Roosevelt himself does not come off scot free. In 1904, it is alleged, Mr. Cornelius Bliss, treasurer of the Republican National party, acting for Mr. Cortelyou, chairman of the Republican National Committee, levied a contribution of £20,000 upon Mr. Henry Rogers and Mr. John Archbold, representing the Standard Oil Company.

In return Mr. Rogers and Mr. Archbold, who have complained that President Roosevelt has been acting harshly towards the Standard Oil Company, were to receive what is called a "Conservative Administration," which, being interpreted, means a Government that will not make things unduly warm for the Standard Oil Company.

On hearing of this Mr. Roosevelt wrote a violent letter to Mr. Cortelyou, denouncing the Standard Oil Company, and directing the return of the £20,000, but - and this is most important - the contributors allege that the money was not returned, and not one cent was paid back.

Not only was it not paid back, but a little later an additional sum of £50,000 was requested from the Standard Oil Company.

Mr. Rogers declined to give any more money, and recalled the fact that the President's instructions to return the first contribution had not been complied with, and that Mr. Roosevelt must have known all along that the £20,000, which he repudiates, had not been only accepted but used.

In view of this fact, Mr. Rogers declined to accede to the request for a further £50,000, and denounced Mr. Roosevelt for seemingly trying, on the one hand, to secure contributions from the Standard Oil Company, and, on the other hand, to make political capital by denouncing the company.

Senator Dupont of Delaware, who is head of the Powder Trust, had to resign from the Chairmanship of the Speaker's Bureau of the Republican National Committee. How many more resignations there will be no one knows. The Standard Oil Company, which Mr. Rockefeller regards with such unfeigned admiration, is not merely a gigantic tnist. Mr. Rockefeller and his partners, the Standard Oil Crowd, control capital many times larger than the national debt. According to Mr. Lewis Emery, who stood for Governor in Pennsylvania, the Standard Oil group, of which Mr. Rockefeller is the head and Mr. Rogers the right hand, hold a controlling interest in the following concerns:-

Insurance companies ............ £280,000,000

Railroads ............................. £500,000,000

Industrial ............................. £360,000,000

Traction and transportation ..... £32,000,000

Gas, electric light, and power ... £22,000,000

Mining companies ................... £39,000,000

Banks and trust companies ...... £36,000,000

Telegraph and telephone ......... £36,000,000

Navigation ............................... £8,000,000

Safe deposits ............................. £120,000

________________________________________________

Total ................................ £1,313,120,000

Here there is an Imperium in imperio, a power within the Republic which Mr. Hearst has now revealed as directly aiming at the control of the Government of the Republic by the use of the money power.

This article appears in Stead's Review, page 327.